The Future of Immigration Reform

June 11, 2015

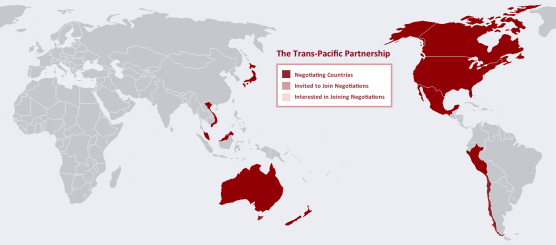

The United States is currently in negotiation to sign a trade agreement with eleven countries, including Mexico and Canada to Vietnam and Malaysia. President Obama’s all-encompassing international regulatory agreement, labeled the TransPacific Partnership (TPP), seeks to regulate everything from the environment and energy to minimum wages, food and, most notably, immigration. If approved, immigration law would no longer be subject to Congressional oversight, but rather be controlled under international law. The administration has requested that Congress give President Obama the power to fast track the Trans-Pacific Partnership. It is still under consideration.

The United States is currently in negotiation to sign a trade agreement with eleven countries, including Mexico and Canada to Vietnam and Malaysia. President Obama’s all-encompassing international regulatory agreement, labeled the TransPacific Partnership (TPP), seeks to regulate everything from the environment and energy to minimum wages, food and, most notably, immigration. If approved, immigration law would no longer be subject to Congressional oversight, but rather be controlled under international law. The administration has requested that Congress give President Obama the power to fast track the Trans-Pacific Partnership. It is still under consideration.

The terms of the TPP require that all laws in the United States, both on state and federal levels, conform to the regulations that the President has described as “rules for the world’s economy.” Although described as a trade agreement, an entire chapter of the TPP is devoted to immigration law, and a representative has confirmed a key feature will be labor mobility. At a summit in March 2015, Obama announced that, “My administration is going to reform the L-1B visa category, which allows corporations to temporarily move workers from a foreign office to a U.S. office in a faster, simpler way. This could benefit hundreds of thousands of nonimmigrant workers and their employers.”

The details of the TransPacific Partnership have been kept secret at this point, with limited access granted to high-level governmental employees; however, this does not leave onlookers entirely in the dark when postulating what the new agreement might discuss. Because every free trade agreement to take effect since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has discussed the movement of workers, with each new agreement providing for the expansion of the type and quantity of workers, it is safe to assume that TPP will do the same.

The 2011 trade agreement between United States and Korea gives an idea of what could be contained in the new agreement. The agreement with Korea established a visa waiver program that gave foreign businesses as much as five years to bring an unlimited number of employees into the U.S. The agreement also provided for unlimited extensions. Using the Korean agreement as precedent, it is likely the TPP will lift restrictions on residency or nationality requirements for workers entering the nation. Immigration provisions of trade agreements similar to the TPP typically permit companies to hire employees anywhere in the world, prohibiting Congress from limiting the number of worker visas. Should the TPP provide enforce similar regulations, the agreement could very well bring the U.S. a step closer to an “open border” policy.